UPSTREAMING UNWANTED MATERIALS STARTING WITH TOXIC GLASS

One of the biggest problems with recycling is that it’s mainly focused on waste streams that are pure and have good structural quality. Think of how you separate glass according to colour at your local recycling station, or cardboard and print paper needs sorting into different bins. Today, waste consists of mixed materials or blends and impure materials with a low chemical structure — often fused with other materials—all things that make recycling harder and impossible. Småland, a county in southern Sweden, is one place where this issue is not only evident but is becoming a severe problem that needs solving. In the mid 20th century, Sweden’s glass industry was booming, admired for its technical engineering and creative techniques employed by the likes of Kosta, Boda, and Åfors. These factories, all located in and around Småland, soon consolidated into one corporation, and their waste fills over 100 landfill sites.

We were called into a large-scale project to examine the potential of the landfill sites in Småland, not just to retrieve the glass and separate it from its toxins but also to open up for new glass production. We worked with the glass research lab at RISE, which leads the project in close collaboration with the County Administrative Boards of Kronoberg and Kalmar counties, recycling company Ragn-Sells, Kingdom of Glass communities Lessebo, Emmaboda, Uppvidinge, and Nybro, and glass manufacturer Målerås Glasbruk. “By taking advantage of the broken glass and manufacturing new products, we make major contributions to the environment. New opportunities to use premises and glass use areas for tourism are also opening up,” said Maria Arnholm and Peter Sandwall, Governors of Kronoberg and Kalmar, respectively. While this project is localised, contaminated glass holds vast scope as a resource on an international level, with new processes for managing contaminated glass from other industries like electronics and mobile devices.

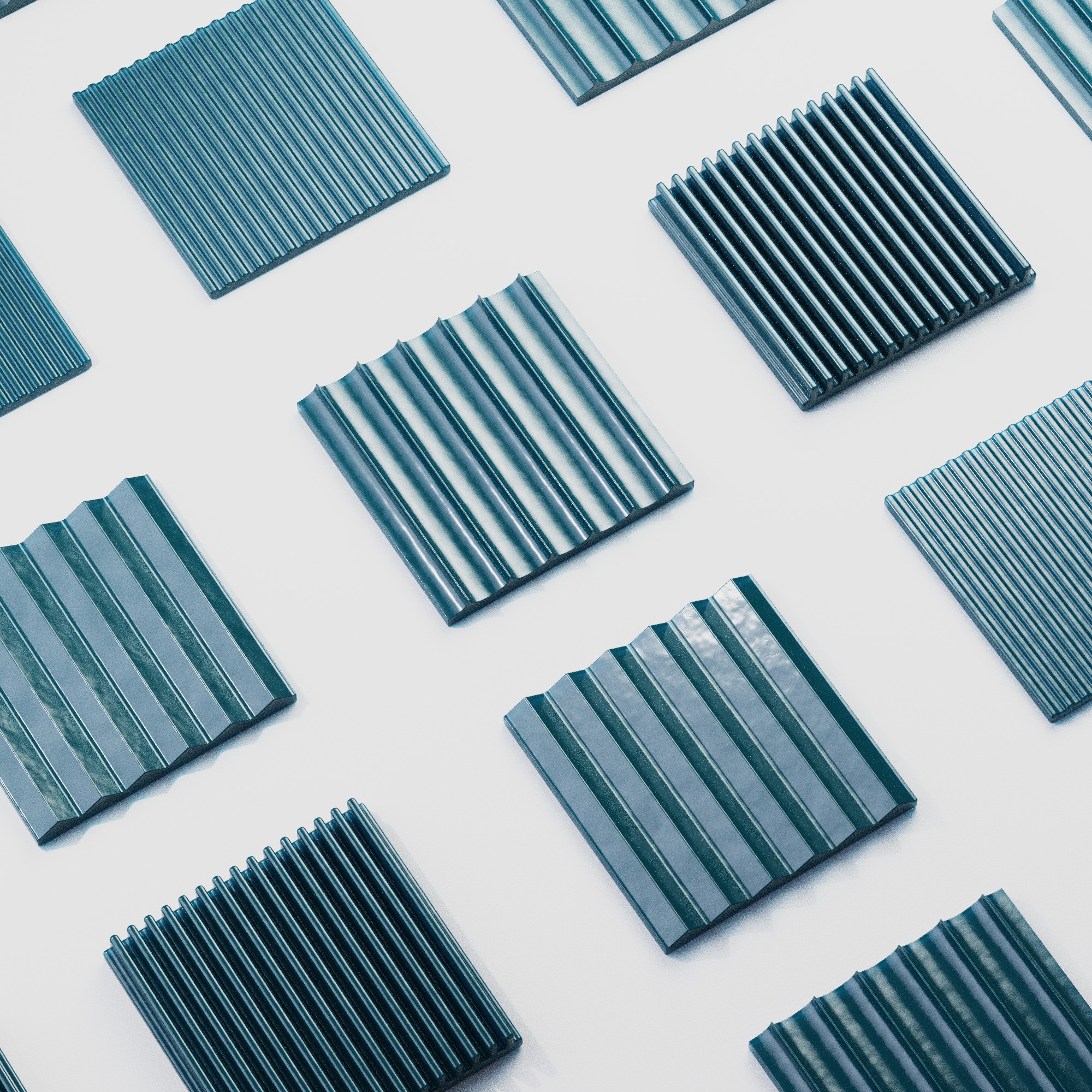

Our specific role in the collaborative project is to seek ways of using the glass and set new benchmarks for how decontaminated glass can be used on an industrial scale. The first product to be launched is one made to be commercially viable, regardless of the scale: a range of glass tiles. The reasoning behind the solution to create glass tiles are numerous. It can be produced easily at scale at a competitive price point. Something versatile that could be used in its simplest form by itself but also scaled up in usage. The tile is made strong enough for facade cladding and elegant enough to be used in interior spaces such as bathrooms or kitchens. The relative ease of a product like this, coupled with the competitive cost margins and unique aesthetic, provides a solid incentive to producers.